Coca-Cola faces a significant sustainability challenge due to its global marketing strategy

Coca-Cola stands as one of the most globally recognized brands. The 2020 commercial featured families drinking Coke with their meals in cities including Orlando, Florida, Shanghai, London, Mexico City, and Mumbai, India, to highlight its global reach, which spans more than 200 nations.

That kind of operation leaves a significant carbon imprint. Every day, the business distributes its goods using more than 200,000 vehicles and operates hundreds of bottling facilities and factories around the world.

But Coke’s refrigeration system is the single factor that contributes the most to global warming.

Electricity is used in large quantities to run freezers, and some of the coolants used in these systems are greenhouse gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. Electricity use accounts for around two thirds of refrigeration’s climatic impact, with refrigerants making up the remaining third. By 2020, refrigeration was responsible for over 8% of all greenhouse gas emissions.

Historical evidence indicates that questioning the necessity of running Coca-Cola’s refrigeration equipment 24/7 at convenience stores worldwide may be the most effective approach to reduce emissions. This unconventional idea challenges the company’s obsession with ensuring Coca-Cola is always readily available, as expressed by one of Coke president as being “an arm’s reach of desire.”

Desired: The ideal refrigerant that meets all criteria

Refrigerants first came under the spotlight as an environmental problem due to worries about ozone depletion, not climate change. Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, were the main coolants used in refrigerators prior to the 1980s. These compounds were found in the 1920s by a chemist at General Motors, and their features of being odorless, nonflammable, and presumably harmless made them helpful to industry. Following then, CFCs took over as the main refrigerant used to maintain temperature.

A gas in the atmosphere called stratospheric ozone, which shields life on Earth from the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation, was later discovered in the 1970s by researchers at the University of California to be susceptible to destruction by CFCs. Through the 1987 Montreal Protocol, one of the most effective environmental treaties ever, nations eventually moved to outlaw the use of CFCs.

New chlorine-free refrigerants, known as hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs, that would not destroy the ozone layer were first promoted by chemical firms like DuPont. HFCs, like CFCs, were attractive to industry due to their lack of inflammability and potential risks to human health.

However, HFCs had a significant disadvantage: as potent greenhouse gases, they retained heat in the atmosphere of the Earth and warmed the surface of the globe. Compared to carbon dioxide, the most prevalent greenhouse gas, some HFCs showed warming effects that were more than 1,000 times larger.

Politics of HFCs: Navigating the Complexities

When companies like Coca-Cola started switching to this new refrigerant in the 1990s, they were aware of the effects HFCs have on the planet’s temperature.

Bryan Jacobs, a Coca-Cola engineer who worked on this transition, in an interview said that early on, refrigeration technicians in Europe recommended another promising path instead.

In Germany, Greenpeace activists and refrigeration experts collaborated closely to create what became known as Greenfreeze cooling equipment: devices that employed hydrocarbons, such as isobutane and propane, as refrigerants. These refrigerants presented the possibility of preserving the ozone layer and the planet because they had a drastically lower global warming impact than HFCs.

Jacobs further added in interview that “pretty dismissive,” largely because his team was concerned that these refrigeration units could blow up, especially in remote places without enough technical support. Coca-Cola changed to HFCs instead.

Greenpeace responded by launching a significant campaign at the 2000 Sydney Olympics to draw attention to how Coca-Cola’s HFC units were contributing to global warming. Coke’s then-CEO, an Australian named Doug Daft, pledged that the business would get rid of HFC refrigeration in the next years

Always within arm’s reach

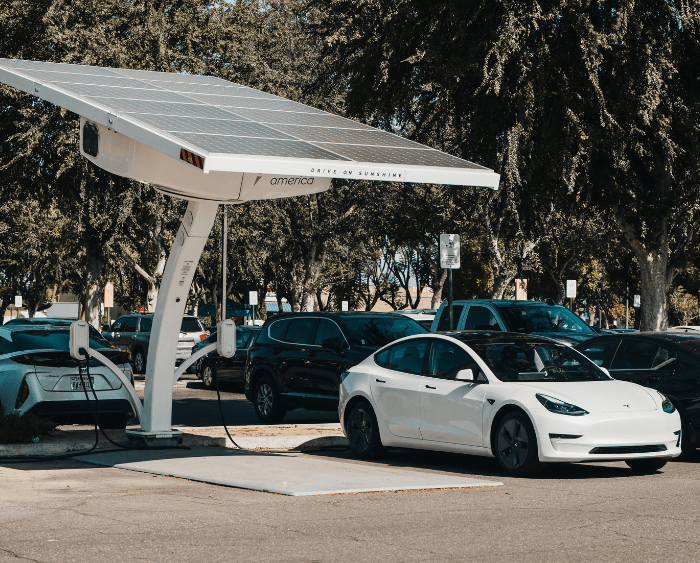

Since 2000, Coca-Cola has established itself as a global innovator in the design of HFC-free refrigeration technology. It first made significant investments in a cutting-edge refrigerator design that utilized carbon dioxide as the primary refrigerant. However, after realizing that hydrocarbon refrigerants weren’t as dangerous as they had first thought, the company soon started using these units as well.

Coca-Cola persuaded additional businesses to stop using HFCs. The company established Refrigerants, Naturally!, an organization dedicated to moving major food and beverage industries towards HFC-free refrigeration, in collaboration with Unilever, Pepsi, Red Bull, and other large corporations. Around 400 consumer products businesses made a commitment to getting rid of HFCs from their refrigeration systems after Coke CEO Muhtar Kent encouraged them to do so in 2010.

By 2016, 61% of all new cooling equipment purchased by Coke was HFC-free, according to the company. That percentage rose to 83% four years later.

Nevertheless, as of 2022, more than 10% of Coke’s new refrigeration units still used HFCs, and this industry’s major source of greenhouse gas emissions was refrigeration. The fact that all of these appliances need power, much of which is produced by burning fossil fuels, contributes to the issue. Keeping Coca-Cola cool still leaves a significant carbon impact due to the company selling about 2.2 billion beverages daily. For Coke’s rivals, the same is true

In an interview, Coca-Cola’s former chief sustainability officer, Jeff Seabright, was asked whether the company had ever contemplated the broader implications of constantly cooling their beverages. Seabright’s response was a resounding “No,” and the corporation continued to be motivated by the maxim of having Coke readily available for consumption at the point of sale.

Despite Coca-Cola’s significant investments in transitioning to alternative refrigerants, their cooling equipment continues to contribute to global warming. It may be time for Coca-Cola to reevaluate the necessity of maintaining a large number of cooling machines, while consumers should also reflect on whether their immediate gratification expectations are worth the environmental consequences they entail.

Conclusion:

Coca-Cola’s global operations, including its extensive distribution network and refrigeration systems, contribute significantly to carbon emissions and global warming. Despite efforts to transition to alternative refrigerants, the company’s cooling equipment remains a major source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Coca-Cola must reconsider the need to maintain a big number of cooling units and look into creative ways to cut emissions in order to address this issue. Customers should take into account how their demands for rapid access to Coca-Cola goods may affect the environment.

Coca-Cola can significantly reduce its carbon footprint by putting sustainability first and investing in more environmentally friendly refrigeration techniques. This will not only be in line with its environmental objectives but also encourage improvement in the sector. In the end, a joint effort between the business and its customers is necessary for a more sustainable future while still being able to enjoy Coca-Cola’s goods.

For more news like this visit Envoybuzz.